fortnite revive meme

At 7.59pm on Christmas Day 2019, a meme was posted to a Facebook page called Memory Lane UK. It was a square, low-resolution image, the kind where a few words of text are layered on top, to be shared, copied, tweaked and reshared. In no fewer than three different fonts, and adorned with two union jack flags and a Facebook logo, it read as follows:

“Memory lane UK

WHO REMEMBERS

proper

binmen”

At 9.16pm that same day – barely a Christmas film later – a second meme was posted, this time a collage of grainy old photos of smiling binmen, insistently asking the same question: “WHO REMEMBERS Proper bin men?” At the time of writing, these two Facebook posts have attracted almost 7,000 likes, 3,000 shares and 900 comments. They were not the first “proper binmen” posts, but they were the first to find a wide audience, and inspired countless imitations.

The first thing you notice about these images – most of which are black and white – are the proper bin men’s outfits. They wear flat caps, donkey jackets and dark trousers or dungarees, rather than hi-vis yellow vests, or overalls marked with reflective stripes and subcontractor logos. The postwar Britain they inhabit looks different, too: from the clunky old bin lorries to the smaller cars in the background. And then there are the bins themselves: cylindrical, metal, plain. Unlike their plastic, colourful modern counterparts, these bins are hoisted on to the bin men’s shoulders.

To their admirers, proper binmen embody a lost postwar idyll – and the decline in national character can be seen in the appalling state of their modern-day counterparts, who are rotten in spirit, in character and in service. The “proper binmen” memes are popular to a degree that may feel initially baffling. They attract phenomenal interest and enthusiasm from older Britons on Facebook, where a whole constellation of meanings and memories are projected on to them: pride, anger, resentment, weariness, ennui and fond, at times very touching, personal recollection.

The proper binmen bestride a wider galaxy of social media nostalgia. The birthplace of the binmen meme, the Memory Lane UK Facebook page, is the sepia-tinted sun at the heart of that galaxy, a community 500,000 followers strong, created on 30 December 2017 by a reclusive Yorkshireman called David Rowding. At the time of writing, Memory Lane UK has a photo of two 1970s Mini 1275 GTs as its Facebook profile picture, and a header photo of claymation icon Morph and his friend Chas.

Though there is nothing generationally unique in the desire to bask in the banalities of your past, these nostalgia communities have flourished on Facebook as its user base has grown ever older in the past decade. There are many rival Facebook groups devoted to commemorating the same mundane aspects of life: The Yesteryears Revisited, Do You Remember This?, I Grew Up In The 1970s, The British Nostalgic Bible, One Hundred and Ten Percent British. Together, these Facebook groups have close to 2 million members: more than the official pages for Labour, the Conservatives and the Lib Dems combined. The baby boomer nostalgia industrial complex is thriving.

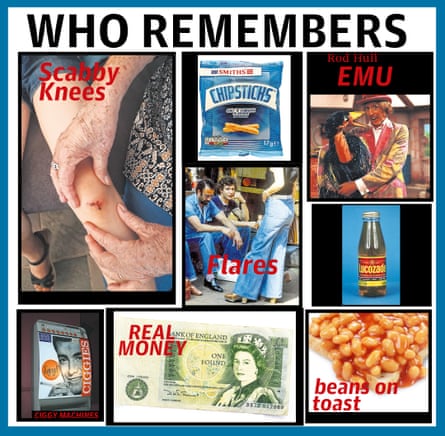

This world, beyond its binmen, is populated with a fascinatingly humdrum array of nostalgic memes. Some are simple injunctions, a few words in all caps – “SHARE IF YOU REMEMBER” – over a picture of Steptoe and Son. Some are presented as questions: “When you were a child, did you have to ask permission to leave the table at the end of a meal?” inscribed over a black-and-white picture of a 1950s family dinner table, dad in his suit and mum wearing a smart hat. Others are bold declarations of fact: “In our day, you only had Lucozade when you were ill.” Such posts acquire levels of engagement that official brand accounts such as Lucozade’s could only dream about. Many posts are wordless, simply displaying an artefact from the reliquary of lost everyday objects, rituals and saints: three-bar electric fires, blackboard erasers, knock down ginger, spud guns, Rod Hull and Emu.

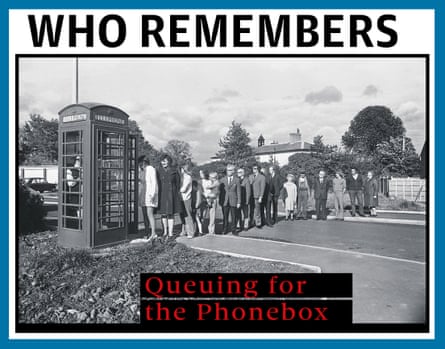

They form a bewildering tableau. Who remembers the cockle man?, ask the memes. Who remembers a dripping sandwich? Who remembers rag and bone men? One pound notes. Drinking water from a hose. Choppers. The saying “act your age, not your shoe size”. Queueing to use a phone box. Playing in the street and yelling “car!”. French cricket. Jam sandwiches. Scabby knees. Skipping. Routemasters. Salt and vinegar Chipsticks. Hot chocolate from the vending machine after swimming lessons. Coal fires. The slipper. The cane. The ruler. Getting a thick ear. Concentrated orange juice. Cumbersome lawnmowers. Traditional drapers. Stand pumps. Ink wells. Duffle coats. Tin baths. Marbles. Jack Charlton. Stevie Nicks. Forgetting your PE kit. Bus conductors. Bob-a-job week. Wooden ice-cream spoons. Snakes and Ladders. Ponchos.

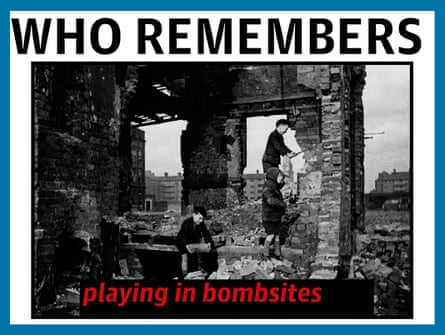

Who still eats beans on toast? Who remembers turning an old sheet into a ghost costume? Who remembers sleepovers? Men opening doors for women? Slow dancing to Nat King Cole. Beech-nut chewing gum. Worzel Gummidge. Sweets by the ounce. Icicles hanging from the window frame (“Before central heating!”). Miss World (“All natural. Not a bit of botox in sight”). The power cuts of 1972-4 (“we coped, we were strong”). Scrubbing and polishing your front steps (“That’s when people had pride in where they lived”). Outdoor toilets. Cigarette machines. Flares. Playing in bombsites. Jumping in puddles. Roland Rat.

There are no births, marriages or deaths here, no wars, no world-historic events, no great men and women of history. There is no post asking “who remembers the Cuban missile crisis?” or “who remembers the sinking of the Belgrano?” Those questions are too remote from ordinary life. Over here, we have abacuses and Listen With Mother to talk about. The banality is the point. This is a world where a picture of three butter knives can attract 1,300 comments of fond recollections and reflections.

When we talk about the past, we always reveal something about the present. It is hard to imagine a more intriguing or overlooked body of evidence for assessing recent British social history than these Facebook groups: they have given us something like a more chaotic, 21st-century version of Mass Observation. They may not be “representative” in any quantifiable way, but the sample size is vast, and these memes are a canvas for a whole range of contemporary insecurities and collective memories. History is written by the winners, but anyone can share a post on Facebook.

Read through the thousands of comments beneath the numerous proper binmen posts and you will find a striking consensus. Back then, in an unspecified period between 1950 and 1980, the binmen were stronger, more hardworking and more polite. Not just that – back then, the binmen were happy. Everyone remembers them the same way: always cheerful, always smiling, frequently whistling. They always had a kind word for you, never complained, and always closed the gate. They took pride in their job, which was hard work, but honest work. These judgments are delivered with absolute certainty. Back then, “They were always a really friendly crowd who you could have a good laugh with,” writes one commenter. “Not like the bin men of today, you are very lucky if they respond to a ‘good morning’.”

The historic shift in bin collection is taken to mark a wider crisis in masculinity. “That is when men were men, not the wimps we have today,” writes one Facebook commenter. “All be off work with PTSD nowadays,” chimes in another. Proper binmen “didn’t care about Health & Safety Shite”, writes another. The plastic wheelie bins we have today – with their emasculating pastels, often colour-coded for recycling, and their humiliating, labour-saving wheels – are just further markers of our moral, social and spiritual decline.

The proper binmen memes are a potent distillation of a sentiment common to contemporary British politics and culture, where politicians have all but given up offering a positive vision of the future, and where the idea of what constitutes progress is bitterly contested. Fond nostalgia for hard times is, of course, not new. In the Monty Python sketch known as the Four Yorkshiremen (classic British comedy), the eponymous characters, clad in bowties and white dinner jackets, reflect on how far they’ve come.

“Who’d a thought 30 years ago we’d all be sittin’ here drinking Chateau de Chassilier wine?”

“Aye. In them days, we’d a’ been glad to have the price of a cup o’ tea.”

“A cup o’ cold tea.”

“Without milk or sugar.

“Or tea!”

“In a filthy, cracked cup.”

“We never used to have a cup. We used to have to drink out of a rolled-up newspaper.”

As the sketch continues, the men summon up increasingly absurd scenarios to one-up each other: “We used to have to get out of the lake at three o’clock in the morning, clean the lake, eat a handful of hot gravel, go to work at t’mill every day for tuppence a month, come home, and Dad would beat us around the head and neck with a broken bottle, if we were lucky!”

The overriding sense from hours of scrolling Facebook nostalgia groups is of a generation who didn’t see that sketch entirely as a joke, so much as a broadly accurate account of their own hard-won triumph over adversity. There are plenty of grim references to old-school bin-collection work being “back-breaking”, and some apparently firsthand binman testimonies specifically refer to having “paid for [the job] with bad backs in later life”. Yet there is a powerful anti-health and safety component to all of the Memory Lane UK reminiscing – against coddling, against rules and red tape, against the easy ride of modern youth. “Remember when your mum would let you lick the egg beaters without anyone freaking out about salmonella?” asks one post. “Remember when we used to play in the dirt?” “Who remembers getting beaten with a cane at school?” We had it tough. We kept calm and carried on. We didn’t complain. We muddled through. We made do. We mended. It never did us any harm. It made us who we are.

Binmenism, as this worldview could be called, is distinct from the common type of nostalgia we are all prone to as we get older – that things were “better in my day”. In fact, the memory lane memes and comment threads make clear that in terms of physical comfort, convenience, domestic labour, work, consumer goods and leisure choice, things used to be worse. But that is not the endpoint of the philosophy. If Binmenism had a motto to stitch on to its itchy old Boy Scout uniform, it would be: things were worse, therefore they were better.

And once you see this, you can’t stop seeing it everywhere.

The deafening siren blaring from the memes themselves is the use of the word “proper”. In an age of fakes, authenticity is everything, so no wonder being “proper” is so highly valued. Everything that has happened since the heyday of proper binmen, the memes imply, has degraded not just the authenticity of binmen, but the authenticity of each of our lives – and the authenticity of Britain itself. Progress is not all it’s cracked up to be. “Wheelie bins came out and the bin men were a bunch o’ jessies,” reflects one Facebook commenter, whose dad was reportedly a proper binman.

The online passion around these unlikely icons of The State of Things is sometimes mirrored in the real world. In recent years, there has been rising abuse, and even violent assaults, against binmen doing their jobs. In 2009, the columnist Richard Littlejohn blamed these violent outbursts on “Elf ‘n’ safety” and “the lunacy of the recycling rules and the Stalinist zeal with which they are enforced”. The column was part of a Daily Mail campaign against wheelie bins, “the plastic monstrosities blighting our streets”, imposed by “bin bureaucrats” hoping to improve recycling. The campaign was announced on the front page with the splash “Not In My Front Yard”. The newspaper’s leader that day described the campaign as “A roar for freedom”. Littlejohn, the prophet who anticipated the online Binmenism that was to follow, wrote that the binmen of his youth had been “Strong men, doing men’s work. The kind of English yeomen you’d always want alongside you in a fight.”

The campaign failed, and the perception of decline has only deepened. In 2016, a video of a nine-year-old girl taking out a wheelie bin deemed too heavy by the binmen went viral. The Mirror reported that the girl’s father “took the footage to embarrass the refuse collectors who, he suggested, had gone soft compared to the binmen of the past”. The following year, a man in Walsall was jailed for assaulting his bin man with a second world war bayonet, after he refused to take a recycling bin contaminated with household waste.

The proper binmen are accompanied by a small supporting cast, such as the “proper football man” – one who is deeply suspicious of statistical analysis and foreign managers in designer coats. The late Lord Stoddart was commended after his death as a “proper Labour man” by Peter Hitchens on account of being a miner’s son, getting into politics through “grammar school and hard work”. Labour MP Wes Streeting has said his was a “proper Labour story”: council estate and state school, to Cambridge University, via McDonald’s, and then to parliament.

Suffering is key to being proper. And Britain’s worsening energy crisis, inflation and inequality have ushered in a fresh wave of lectures on the moral benefits of suffering. Stern voices have clamoured to remind us that being dangerously cold, being desperately poor and enduring powercuts, broken supply chains, food shortages and cold baths has happened to Britons before, and it would probably do us good, if anything, if it happened again.

For the rich and powerful, this is a handy philosophy: they are rarely the ones enduring the pain. In February, Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, whose annual salary is more than £570,000, told workers they should not demand higher wages, in order to contain inflation. In May, then-food and farming minister George Eustice told people they should buy value brands to “contain and manage their household budget”. “Blackouts,” wrote Telegraph columnist Robert Taylor in October, recalling the powercuts of 1973, “could be just the ticket to shake some of today’s youngsters out of that sublime sense of entitlement and self-righteousness.”

From the Covid pandemic and lockdowns to the cost of living crisis, it seems that the harder the challenges of contemporary British life become, the more we are encouraged to suck it up, and channel the hardships of yore – usually by people who did not experience those hardships themselves. Since the start of 2020, “the blitz” has clocked up 37 references in Hansard, the official parliamentary record – only 11 shy of the 48 citations in parliament during the whole of 1940 and 1941, when the blitz was actually taking place. The first reference in Hansard to the famed “blitz spirit” was not until 1972. The phrase was not used again until 1999. But since 2000, it has appeared six times. The further away we get from the Nazi blitzkrieg, the more we are asked to revive the “spirit” of the time.

Underpinning this celebration of suffering is the masochistic idea that it is your individual responsibility – indeed an important test of your character – to withstand ruinous social and economic crises not of your making. It is there in Keir Starmer ventriloquising a dead monarch to a proper bin man’s tune, with his advice on how the poorest Britons should deal with an economic situation that could very possibly kill them this winter: the Queen “would urge us to turn our collar up and face the storm”.

Elizabeth II herself was, we can reasonably assume from the tributes which followed her death, a proper Queen. Under the headline “The Queen’s 1950s frugality is key to our future”, one Times columnist praised her for being “naturally parsimonious”, personifying not obscene wealth and the plundered spoils of Empire, but the halcyon moment of High Binmenism, at some point in the 1950s, before the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ first LP. “In this age of Amazon Prime and Kim Kardashian-style super-rich spending, her frugality may seem quaint,” Alice Thomson wrote, “but it feels timely. As the cost of living crisis hits, everyone is looking for ways to cut back, taking a Thermos of coffee to work, eating leftovers for lunch and sewing on lost buttons.” That even a literal Queen has to be explained in this way suggests how deep Binmenism goes.

The battle to define what counts as “progress” is always fraught, not least because it is usually up to our political leaders to shape that narrative. For this reason alone, it is worth remembering that not all “progress” is necessarily good, and not everyone who queries the official narrative of progress is wrong. It doesn’t mean they are right, either.

Alongside their mission to excavate the rubble of the past, the Facebook nostalgia communities often pour scorn on the objects and rituals of today’s zeitgeist, in particular the damage done by technology. Computer games, smartphones, social media and TV are seen to create a disenchanted childhood, lacking in imagination, adventure and risk. The Binmenists’ grandchildren are alternately pitied and condemned: “I’m so glad I grew up before technology took over” is a recurring slogan, placed over a black-and-white photo of old-fashioned youthful horseplay. “Fresh air in the lungs instead of playing Fortnite,” recalls one commenter of their own childhood. “Not a computer in sight!” runs another near-catchphrase (posted, presumably, via computer).

Social media allows baby boomers to see the lives of their children and grandchildren in a way that was always partially concealed from them in the past. In response, they resurrect their own, very different cultural treasures and experiences. While some of the Memory Lane UK posts and comments seem to be motivated by a hostility to technological change or a bureaucratic nanny state, others speak to something deeper: to a vindication of the existence and survival of the person posting them. In one poignant meme, over an old photo of a rusty playground slide, inscribed in capital letters is the question: “WE SURVIVED DIDN’T WE?” On the surface, it’s about not being killed by poor-quality playground equipment. But perhaps it’s also about the solidarity of making it to late-middle or old age – perhaps a little disbelief too, along with the pride and relief. We made it this far.

Under the surface, there also lurks that Four Yorkshiremen-style macho-masochism: things were worse, therefore better. It is probably no great surprise that posts calling for the return of national service are overwhelmingly popular in the Memory Lane UK universe, but reading through the comments, their advocates seem uninterested in gung-ho militarism for its own sake, or restoring the British army or empire to their height. A zeal for the equalising, toughening effects of physical pain and hardship is the key recurring theme. In one Memory Lane UK meme, images of the binmen show up in a video slideshow alongside black-and-white photos of children playing in the mud, smoking, overloading see-saws and peering down open drains. The video is titled Little Trip Down Memory Lane – Before Health and Safety Took Over. Pain is a rite of passage, and anyone who sidesteps it will fail to become a proper adult.

The vitality of the nostalgia industrial complex is a reminder of just how appealing it is to have your private reminiscences, buried memories and hazy childhood images validated by others – whatever your age. It is a source of comfort to know you are not mistaken, that your version of your life’s story is shared. Accompanying this is an anxious doubt about not having your experiences, especially your hardships, taken seriously. As Michael Palin says at the end of the Four Yorkshiremen sketch, after the men have reached an absurd climax in their arms race of childhood suffering: “You try and tell the young people today that … and they won’t believe you!”

“We turn to the past when the future seems unattainable or utopian,” Patrick Wright wrote in his 1985 book on British heritage, history and collective memory, On Living in an Old Country. Public malaise with the political establishment, the atomising effects of neoliberalism and austerity, and the dark threat of the climate crisis all make it harder to have faith in the future. Our gaze seems to inevitably turn backwards. The politics of the past few years abound with a desire for a return to an imagined, halcyon former version of Britain. This is true of both sides of the Brexit referendum; for remainers, there is often wistful talk of the 2012 Olympic opening ceremony or the New Labour period, while Brexiteers look back further into history.

Brexit, like the Memory Lane UK posts, partly speaks to an existential sadness about the passage of time and the desire for revenge on what we imagine it has done to us. You can only take back control if you have become convinced you once had it, and have had it torn from your grasp. “The nativist promise,” Simon Kuper observed recently, “is that the betrayal can be reversed, that one day it will be bright, sunny 1955 again.” The twist, of course, is that for Binmenists, 1955 wasn’t even that bright and sunny: things were worse, and therefore better.

But even that strange twist – worse, therefore better – has an underlying logic to it. The political economist William Davies has described the way people who feel disenfranchised often find solace in nationalism. He writes: “The nationalist leader holds out the promise of restoring things to how they were, including all the forms of brutality – such as capital punishment, back-breaking physical work, patriarchal domination – that social progress had consigned to history. For reasons Freud would have understood, this isn’t as simple as wanting life to be more pleasurable, but a deep desire to restore a political order that made sense, in spite of its harshness. It is a rejection of progress in all its forms.”

Sometimes these Facebook groups comment explicitly on what is happening in Britain right now. When they do, they often channel the kind of grievance politics that animated the Brexit vote, all stitched into the “grey curtain of reaction” described by the late writer Mark Fisher: the grim cynicism and negative solidarity that characterises much of the past 40 years of British politics. For example, for most of 2021, Memory Lane UK’s pinned post was a conspiratorial anti-mask post with 1.5k likes, 2.9k comments and 1.4k shares.

In another Facebook nostalgia group, Britain’s history and its present concerns overlap directly. If you search for the word “history” in the One Hundred and Ten Percent British group, there are several coded – and several entirely uncoded – racist memes. One decries the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston (it’s been there for 100 years, so how could it be offensive?); another the way the history of slavery is discussed (Britain cannot be racist because of how expensive its Slavery Abolition Act was); another condemns Black Lives Matter (“I refuse to kneel for a criminal thug,” says one commenter of George Floyd). There is also a very popular meme that crops up repeatedly: the words “SHARE THIS IF YOU THINK BRITISH HISTORY SHOULD BE TAUGHT IN SCHOOLS AGAIN!” alongside an illustration of the signing of Magna Carta. After it was posted on 30 December 2019, 8,300 people duly shared it in approval of the idea of teaching British history in schools “again”.

And yet, not everything in the Binmenists’ world is so easily slotted into stereotypes of the socially conservative, curtain-twitching older voter. Also on display is a kind of humanist libertarianism, a strain of everyday British political life that persists beneath the sound and fury of the rightwing press. Under a Memory Lane UK post of a small child learning to a ride a motorcycle, which reads “Teach them to change gears NOT GENDERS”, the majority of the most popular comments respond with sentiments along the lines of “live and let live”. And when black England footballers who had missed penalties in 2021’s European Championship final received torrents of racist abuse online, the Memory Lane UK community responded with strident messages of solidarity: “Racists do not speak for me. I am proud these men represent my country!” declared one meme.

If we are honest with ourselves, perhaps we are all prone to the odd Four Yorkshiremen-like moments. We all have memories we cling to, and all want to feel like the stories of how we got here have been heard: to remind ourselves and others that the smallest details of our pasts are worth recording. Our memories are fallible at the best of times, and the way we narrate our own lives can often be partial versions of the truth.

As a widely discussed LSE report into class identity made clear last year, people are capable of telling themselves some remarkable tall tales about their own upbringing and class position. The LSE researchers interviewed successful TV producers, actors and architects who all brushed aside their own private schooling, housing security and material privilege to foreground a single grandparent who was a coal miner. These are the myths many British people tell themselves – channelling Lonnie Donegan’s smash hit No 1 single, My Old Man’s a Dustman, that their fathers also wore cor blimey trousers and lived in a council flat.

Whether our images of worse-but-better times are accurate, or just scrappy patchworks of meme, myth and memory, they are deeply ingrained. It is not good enough to merely dismiss the Facebook nostalgics’ sepia-tinted version of history out of hand, if you care about Britain today. The proper binmen are living inside many of us, pulling our strings and guiding us not just down memory lane, but into the future.